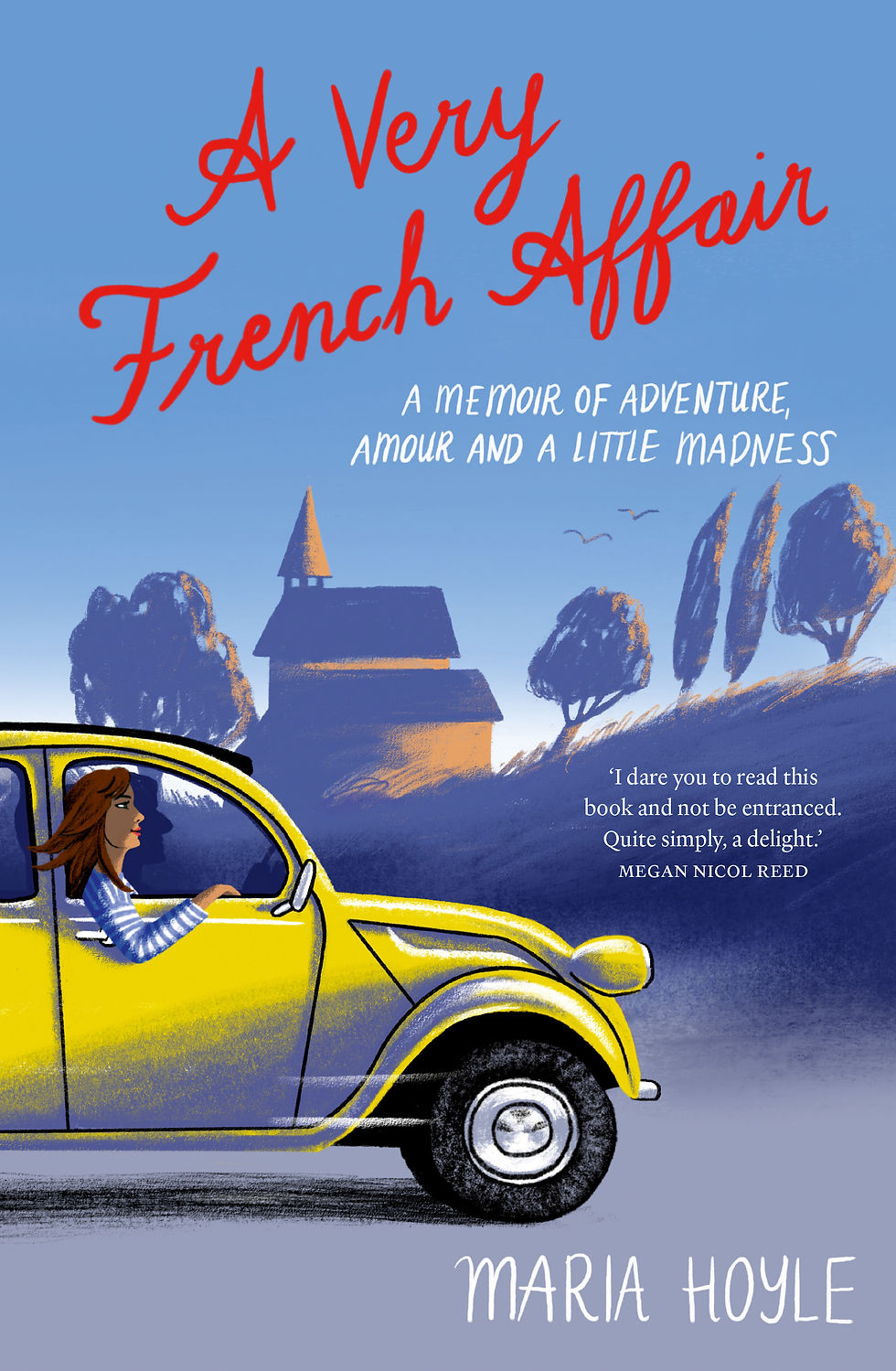

Read an extract of A Very French Affair by Maria Hoyle.

1

Running Away to the Circus

The air is warm and gentle, and the evening does what long, balmy summer evenings will. It casts a spell. Not that it needs to — this rural French setting is enchanting enough.

We’re in the grounds of a manor house — a grand edifice that’s peeling and faded but all the more charming for it. A makeshift bar runs across the great entrance to the house, selling wine, beer and plates of cured ham, cheese and bread still warm from the oven. The eccentric outdoor lighting — over-sized modern lampshades on wooden stands placed at intervals on the lawn — casts a glow over the scene.

We sip and we chat, heady on wine and excitement. Dogs stare hopefully at half-empty plates, and children squeal and chase one another among the wooden tables. On this sultry August evening, in a place that is more dimly lit theatre set than garden, it’s easy to believe in magic, in ghosts, in a night without end.

The manor house belonged to an old lady who stipulated that, on her death, it must never be sold but used for the public good. Its current residents are a troupe of actors who, in exchange for a peppercorn rent, perform shows throughout summer. In a yurt in the next field a ‘circus’ is to take place. Not a traditional circus but — it turns out — a theatre of the mind, where a simple trio of performers fires up our dormant imaginations, and we are all six years old again. On a tiny wooden stage, in the middle of a field, in the rural depths of France, I am transported. But then I already was.

I am living an existence I could barely have dreamed of five months ago. Back then, I was content enough with my life in Auckland. Content but also exhausted from surviving in an expensive city. It was a circus of sorts, and I was the resident juggler. How, I would think to myself, did I get to 63 and still find myself renting, working full-time, yet struggling to make ends meet? I was immensely grateful for my amazing daughters and friends. I was fully aware that my humdrum routine of Wordle, dog walks and early nights with my book was something families in war zones could only dream of. But I was also guiltily ponderng: is this all there is?

I was online ‘dating’ — if you can call it that. You know, just in case. The same way some agnostics occasionally go to church. In truth I didn’t really see the point anymore. Married for seven years and now divorced, my past was littered with dashed hopes and failed romances . . . ex, ex, ex, ex, ex, ex — like a row of cold kisses.

It’s a wonder I was only slightly bruised and not wholly broken. I’d survived narcissists, depressives, control freaks and alcoholics. (Some people were all these things at once.) It’s not that I am flawless — heavens no. But I was spectacularly gifted at choosing men who’d flatter the bejesus out of me then inevitably, some months later, express disappointment that I wasn’t quite what they signed up for. In other words, that the five-foot package of positivity and delight they first encountered was showing herself to be something quite other — a woman with emotions, scars and needs. That regrettably, because of this, I wasn’t a fit for the role they’d had in mind. Consequently, going forwards, they felt cheerful and optimistic about the viability of their personal business without me.

My latest round of online dating only confirmed my worst suspicions. Every snapper-holding, singlet-wearing, Harley-straddling male deepened my despair. Every page of ghastly misspellings and arrogant list of deal-breakers (right up there ‘must be drama-free’) made my heart sink a little further.

And then I met Alistair.

—————

We messaged each other intermittently, with weeks of silence in between. Then one night he left me a voicemail — and that was it. Some people have a thing about teeth, others hands, hair or a way of walking. For me it’s voices. Alistair’s was an exceptionally pleasant baritone — smooth and playful.

I also liked his approach to life, especially now that we had a lot less of it ahead. Alistair had an explorer’s spirit. He wanted to roam and discover — both geographically and in every other sense. He talked about Buddhism and spiritual growth, about travelling and trying new things. He exuded curiosity and dynamism, and I felt that in his company I could expand, not shrivel, as I aged.

He invited me to visit him in Nelson, in the South Island of New Zealand, where he was living until his move to France later in the year. He’d been in New Zealand for fifteen years but now his Irish–English roots beckoned and he was ready to go back to the northern hemisphere. ‘I own a mill by a river in France,’ he told me. ‘Of course you do,’ I said. Then I realised he meant it.

His return had been delayed because of Covid travel restrictions and he was eager to be reunited with this ‘truly special, magical’ place. Alistair told me all this straight away, so I knew it would be an extremely brief liaison. But I still had to go and meet him. Because, well, live for the moment, right? Besides, he fascinated me.

The two weekends we spent together were idyllic. E-bike rides, long lunches, afternoons lying on the grass down by the stream on his property, so much laughing and talking. But when he said ‘Why don’t you come to France too?’ it seemed insane. Nuts. Bonkers. People did that in romcoms. People who looked like Julia Roberts and Marion Cotillard did that. Not your average copywriter nearing retirement. Besides, the romantic prognosis wasn’t great. I was easily triggered, way too sensitive for my own good and terrible at intimacy. Not sex, but real intimacy. By what logic, then, did this have a chance of succeeding?

Yet what seemed more lunatic was the notion of spending my remaining healthy years in exactly the same way I had been doing for decades. Doing the nine-to-five grind, always short of money, living in the exact same postcode, with the exact same routine. The more I thought about France, the more sense it made.

I’d grown up in the UK, had family and friends in Europe, spoke French (rustily) and had no house to sell nor swathes of possessions to put in storage.

So I made up my mind to go and began cheerfully (somewhat hysterically) proclaiming to anyone who’d listen, ‘Guess what? I’m off to Fraaance!’ Without exception they marvelled at my courage, and I basked in their marvelling. Suddenly I wasn’t just Maria the short lady with a dog. I was Maria the Brave. Maria with a Plane Ticket to Paris.

Everyone was rooting for me. Even my employer was on board. I went into a Zoom meeting thinking I was about to resign from a job I loved, only to have my manager tell me: ‘No, wait. We can make this work. You can’t say no to an opportunity like this!’ We agreed I’d work part-time, remotely. This type of encouragement — often sprinkled with ‘Just do it,’ and ‘Oh wow, what an opportunity!’ — began to dismantle the barriers to making this huge life change.

In my heightened emotional state and believing my own ridiculous PR, if I’d been asked to pen an official press release on my decision, it would have gone something like this:

‘I want to prove that life — even in the third act — can still take surprising turns. That you can look forward to more than cheap bus fares and discounted movie tickets. That love is not only still possible, but it can be the best love you ever had. That maturity doesn’t need to be a stagnant pool where expectations go to die. It can be more like the river rushing below the windows of Alistair’s beloved mill — ever flowing, swirling, playing and tumbling towards its final destination. That — health allowing — you don’t need to do a slow fade but can live each day in glorious technicolour.’

Ha.

Extracted from A Very French Affair by Maria Hoyle.

A Very French Affair

by Maria Hoyle

A transcontinental, romantic memoir in the vein of A Year in Provence and Eat, Pray, Love.

Comments